The Rudderless Management of Canadian Federal Cyber Security

There is a reason Canada's cyber security feels rudderless: it is

Canadian Cyber in Context is sponsored by

All views expressed belong to Canadian Cyber in Context and do not reflect the position of any sponsor.

Have your business logo featured in Canadian Cyber in Context with a sponsorship.

On 21 October 2025, the Auditor General of Canada released the report Cyber Security of Government Networks and Systems: Gaps exist in the federal government’s approach to defending against cyber security threats. On its release, the report received considerable attention from some of Canada’s top news agencies, including CBC News and The Canadian Press.

My reaction was simple: “Oh, cool, maybe the government will finally address these issues I’ve been talking about since 2022.” The report was not a surprise to myself and others, and I was actually a little surprised it was not more scathing. By all means, the report wasn’t that bad. The good news is that Canada’s cybersecurity capabilities are well-regarded and advanced, but the application and management of cybersecurity across the Government of Canada remain inconsistent.

I unfortunately have been wrapped up and busy with various other projects and work since October, so I have not had the time to write up an analysis of an audit. Now better late than never…

What Does the Report Say?

The audit examined the 2022 to 2024 calendar years and selected 8 post-cyber security events to examine in further detail. As the audit primarily focused on day-to-day cyber security operations, the audit focused on the Treasury Board Secretriat (TBS), Communications Security Establishment (CSE)/Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (CCCS), and Shared Services Canada. The Auditor General notes that Canada' has the tools and capabilities to protect the federal government from cyber threats. However, there remain major gaps in the adoption of these services and tools, monitoring capabilities, incomplete inventories, and coordination in response to incidents.

CSE/CCCS responded to 1,017 incidents in the 2023-24 fiscal year period examined by the Auditor General, two of which were the January 2024 attack on Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and the March 2024 attack on FINTRAC. An “incident” can be both large and small, so the number itself does not say much, but most of them will not be on the same level as the GAC and FINTRAC attacks. Nevertheless, there is a chance that there are other major incidents that we have not heard about.

The Good

The Enterprise Cyber Security Strategy is sound (I wrote an overview of it here)

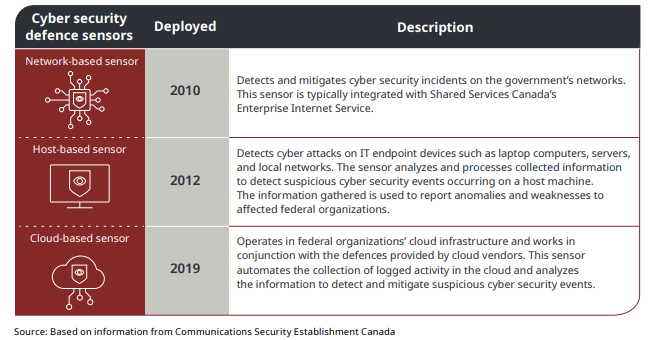

CSE’s network/host/cloud-based sensors are great (So great that the UK government have used some of them since 2020).

SSC’s Enterprise Internet Service is also very well regarded

The Bad

Not all of the government uses the CSE sensors or SSC’s Enterprise Internet Service

Coordination, especially during security incidents, is not good

SSC has an incomplete inventory of IT assets under its responsibility

Phishing remains one of the primary means for initial access, which continues to highlight the need for a workforce trained and aware of cyber security.

Rise in attacks via VPN is an increasing risk for federal government

The overall assessment from the audit gives the impression of a generally good cyber security operations across the government, but gaps remain in large part due to poor coordination a lack of active management of Canadian cyber security at the political level.

Federal Cyber Security Management by Committee

At the center of the Auditor General’s report is that you have at least 4 ministries/federal organizations that have a major role in the management of federal cyber security. This report reminds me of a paper I once read that tried to argue that Canada has centralized the governance of cyber security. Well, as I am about to show you, this is not the case at all and is almost the opposite of how Canada approaches. It is a common misconception that Public Safety Canada is the government lead on cybersecurity. Officially, Public Safety Canada serves as the “national cyber security policy lead,” but its day-to-day operational role is quite minimal (if you exclude the RCMP). There is even an argument to be made that they normally follow the lead of the government’s primary day-to-day operational cybersecurity organizations: TBS, SSC, and CSE/CCCS.

Each of organization have a separate operational role:

TBS: Policy leadership, establishes government-wide cyber security policy and direction such as the Policy on Service and Digital and Enterprise Cyber Security Strategy.

SSC: Are the primary day-to-day builders and operators of the federal government’s networks and maintain most of the government’s IT infrastructure.

CSE/CCCS: CSE, primarily through the CCCS, are the federal government’s lead on cyber security and often advises the government, other ministries, and the public on cyber security.

Each of these organizations operate within their respective silos and areas, but also work closely on a daily basis to manage the federal government’s massive information network. At the highest levels, the Deputy Minister’ Committee on Cyber Security1 (DM Cyber Security) and the Assistant Deputy Minister’s Cyber Security Committee2 (ADM Cyber Security), who have a mandate “to develop and lead Canada’s cyber security policies and operations in support of the government’s economic and social priorities.” DM Cyber Security’s primary activities are:

“identify policy, legislative and program opportunities to ensure that Canada’s 21st-century digital economy is secure by design, and that Canada is recognized internationally for leadership on cyber security issues; and

oversee the evolution and progress of the implementation of Canada’s National Cyber Security Strategy.”

These committees are co-chaired by Public Safety Canada and CSE, which is one of the only actual operational leadership roles held by Public Safety Canada in federal cyber security management. Not to be outdone, there is also the Deputy Minister Committee on Enterprise Priorities and Planning, which is concerned with the management and service delivery of information technology. This differs from DM Cyber Security, which deals a lot more with planning whereas DM Cyber Security focuses on coordination between ministries and government organizations.

Auditor’s Recommendations & Gov Responses

The Auditor General has five recommendations for the Government of Canada and the associated organizations all agreed, with additional commentary provided related to this agreement:

SSC and CSE should develop a Security Information and Event Management application to help address the current gaps in cyber security monitoring.

SSC agreed and said they are completing the procurement

SSC should ensure that it has an up-to-date inventory, which SSC agreed.

Honestly, SSC shouldn’t feel too bad about this one as almost EVERYONE has incomplete inventories of their IT assets. Nevertheless, this is not an excuse and it’s integral to security to ensure you know where all your IT assets are.

TBS and CSE should ensure all federal organizations implement CSE sensors on IT endpoints so vulnerabilities can be identified; and to remediate vulnerabilities in a timely manner.

Additional response boils down to TBS and CSE will deploy more sensors across the government, which will be helped by SSC’s Endpoint Visibility, Awareness and Security Initiative.

TBS, SSC, and CSE should re-evaluate their cyber security incident management practices to improve coordination and timely sharing.

They all agreed and mentioned they will even be testing the Government of Canada Cyber Security Event Management Plan (GC CSEMP) via a cyber simulation exercise. CCCS is also currently developing a “GC-wide cyber security event collaboration platform and incident case management tool,” which should help with this as well.

CSE should prioritize and finalize its funding request and build the GC-wide cyber security event collaboration platform.

CSE agreed, but did not have a timeline for this, because it is subject to “government decision-making.”

Much of this is the overarching points, but ultimately do recommend reading the report as it gives a good idea how the government manages cyber security operations in a way you will not normally understand from other government documents.

So What? - Takeaways

Despite the headlines, the audit was not that bad and is much of what we would have expected, if not better. Most of the major issues appear to stem from poor management and coordination and the day-to-day management of Canadian federal cyber security is quite sound.

I have long complained that I do not like the management of Canadian cyber security by committee and this audit does a good job of highlighting why this is the case. Effectively, there is no political leadership by the Government of Canada and it is predominantly led by unelected officials through committees. The benefit to this is that a lot of experts have lead roles in the broader management and oversight of cyber security, which is what we want. The downside is that you effectively have four ministers responsible for Canadian cyber security: Minister of Government Transformation, Public Services and Procurement Joël Lightbound is in charge of SSC, Minister of National Defence David McGuinty is in charge of CSE, Shafqat Ali is President of the TBS, and Minister of Public Safety Gary Anandasangaree is in charge of Public Safety Canada.

This begs the question: who’s in charge of Canadian cyber security? The government and many are likely to say Public Safety Canada, as they are the policy lead, but its only leadership roles are as co-chair of the DM Cyber Security Committee, the Federal Cyber Incident Response Plan, and the Canadian Cyber Defence Collective Strategic Forum. These committees largely have a coordinating function, which means they’re less of a leadership role and are more so overseeing the coordination, as they have no active role in the operations.

Public Safety Canada remaining the policy lead is likely a holdover from when it had the Canadian Cyber Incident Response Centre, which was transferred to the CCCS in 2018. After 2018, Public Safety Canada has had only a high-level policy coordination role, so it must be questioned as to what is even Public Safety Canada’s role in Canadian cyber security policy? To what degree is Public Safety heeded over the cyber security experts at CSE/CCCS? To what degree is government policy that is set by TBS determined by Public Safety Canada over the recommendations of SSC or CSE/CCCS? This is not to say that Public Safety Canada does not contribute or have great people working in policy and cyber crime, but at what point are we saying they are the government’s cyber security policy lead because no one else wants to hold the pen?

In the end, if Public Safety Canada dictates a new cyber security policy, it only happens because TBS, SSC, and CSE agree with it. The lack of movement on major ICT capabilities and projects, especially ones highlighted by the Audit, such as the SIEM project put on hold in June 2024, suggests political leadership has a gross misunderstanding of cybersecurity and is not providing the tools necessary for TBS, SSC, and CSE.

Canada’s government needs to have a hard look at how it is managing cyber security and recognize that it continues to treat cyber security as not a priority as long as there is no political leadership addressing federal cyber security.

CSE Sensors for All

Time and again, every audit, report, and review of CSE’s sensors says nothing but glowing, positive things about them. TBS policies only require that 85 federal organizations of 204 must use CSE sensors and SSC’s Enterprise Internet Service. Although many organizations voluntarily sign up for the sensors, this audit proves that it is not time to mandate these defences across all of the government.

SSC and CSE/CCCS have a massive federal government IT network and assets to protect, so it is not surprising that there would be gaps. The report notes that SSC and CSE/CCCS have significant capabilities and expertise, which is expected to improve further with the Auditor General’s recommendations. A significant opportunity exists to think beyond these immediate steps and beyond the Enterprise Cyber Security Strategy and determine what are the next steps to modernize the federal government’s cyber security operations from siloed to holistic and centralized.

However, this type of thinking will have to come from the bureaucrats and experts in TBS, SSC, and CSE/CCCS because the latest National Cyber Security Strategy and limited funding for the strategy do not give the impression that the current government is thinking about cyber security in any way other than how to increase private investments into the sector.

DM Cyber Security consists of 14 organizations including: CSE, TBS, Public Safety Canada, Privy Council Office, CSIS, DND/CAF, RCMP, Health Canada, Natural Resources Canada, Transport Canada, Department of Finance, and ISED. (It is not listed in the source, but Global Affairs Canada is likely part of this too)

Although ADM Cyber Security is primary a support body to DM Cyber Security, it also has the additional purposes of: guide policy direction and operations for issues related to cyber security; develop cyber security-related priorities for member departments and agencies; monitor progress on the implementation of Canada’s National Cyber Security Strategy; consider emerging cyber issues and threats; and review and prepare items for DM Cyber Security.

"The common theme was surprise that the..."

<The lights went out, there was a scream>

For some reason the email I received and the post here in substack is missing something? I can guess and fill in the blanks but perhaps I should not.

Alex — your piece does a good job of describing the symptoms of Canada’s federal cyber challenge: fragmented implementation, committee-heavy governance, and an absence of decisive leadership. Where I think it misses an important dimension is why many departments are structurally resistant to the kind of centralized direction you’re calling for.

That resistance isn’t ignorance or inertia. It’s the product of history and governance design.

In the early-2000s, when I was establishing Managed Security Services at CGI, industry providers were aggregating operational security telemetry on behalf of roughly 45 federal departments. During that period, Communications Security Establishment approached industry requesting access to the aggregated data.

The response was straightforward and non-ideological: we could not provide that data without violating dozens of departmental contracts. Each department was — and remains — the data owner and the risk authority. If CSE wanted access, it needed to seek consent from the participating departments directly.

That did not happen.

What followed were candid discussions across the Canadian security community, many convened under the Standards Council of Canada, where a clear position was established: industry would not bypass departmental authority, contractual obligations, or consent models in response to centrally framed requests, regardless of intent.

That episode matters because it hardened a lesson departments have not forgotten:

Central visibility without explicit authority, consent, and accountability is not leadership — it is unmanaged risk.

This history also aligns directly with how Treasury Board Secretariat security policy actually works — a point often missed in calls for stronger central control.

TBS does not direct departments to implement security in a prescriptive or operational way. It establishes overarching policy objectives, principles, and expectations, and deliberately leaves implementation to departments. That is by design. Departments remain accountable for their own systems, data, and risk decisions, and they are expected to adopt policy in ways that fit their mandate, threat profile, and legal obligations.

In other words, departments are not ignoring leadership; they are operating within the governance model Parliament and Treasury Board have chosen.

This is why arguments that Canada’s cyber posture could be fixed if a central actor simply “took charge” fail to resonate internally. They collide with two enduring realities:

CSE does not have standing authority to compel departmental data sharing, and history has reinforced caution around informal or implied expansion of mandate.

TBS security policy is enabling, not coercive — it defines the what and why, not the how, where, or with whom data is shared.

So yes, the federal cyber system lacks coherence. But the solution is not stronger assertion within existing boundaries. It is clearer authority, explicit consent models, and governance mechanisms that respect departmental ownership by construction rather than by reassurance.

Until that foundation exists, skepticism toward centralization isn’t obstructionism — it’s responsible governance informed by experience.